In recent gaming news Microsoft wielded the banhammer upon gamers using swastikas in their logos, sparking some discussions about symbols and freedom of expression and whatnot, and reminding me of a topic I used for a bible study at martial arts class awhile back.

What is a symbol? It can be a source of pride and power for those who believe in it, or cause for disdain or even anger for those who disagree with it. It may be created with one meaning in mind and then be bestowed and/or burdened with many more, complimentary or contradictory. In some ways a symbol is just an inanimate object with no real power beyond what people choose to attribute to it, yet at the same time everyone can think of some point in their lives when they were inspired, disgusted, saddened, emboldened, or otherwise moved by a symbol.

The world is fair teeming with symbols, efficient communication at its best (usually). A family crest tells a snapshot of your lineage with an artistic flair. Back in the day military units prominently displayed easily visible emblems to ensure people weren’t shooting their own men. A memorable company logo slapped on hats and t-shirts can turn fans of your products into walking advertisements. (I recall once hearing of a study warning that children quizzed were more able to identify ten corporate logos than they could identify ten common types of plants, to which I thought that I’d have an easier time identifying plants if they grew in the shape of their names, but I digress). Jewlery such as earrings, pendants, rings, watches and others are often given as gifts to symbolize a bond between people. Tattoo artists can engrave the symbols that define you right into your skin. And then there’s that grand old flag.

Until moonvertising catches on, a flag is arguably one of the mightiest ways to wield a symbol. A symbol you wear can usually be hidden and then taken back out later when it’s convenient, and tends to only be visible to whoever’s right by you. To use a flag properly you have to run it up a flagpole and let it fly high in the wind where everyone can see it. People will come who disagree with your flag and will want to show their disagreement by taking down your flag because to attack your symbol is to symbolically attack what the symbol stands for. Flags are serious business.

Though technically not a flag, there’s a flag-like-object-related scene in the movie Kingdom of Heaven. At one point Balian is leading a suicide charge with a handful of crusaders to defend a small city from an overwhelmingly massive saracen force. When it looks like the dwindling survivors are done for, a gleam of light is seen far in the distance. Across the boiling sands, a great golden glowing cross is seen to rise from the desert, looming towards the battlefield. As it draws closer it’s revealed to be an actual tremendous gold-plated cross carried to herald Jerusalem’s army.

When that glow first appeared in the distance I was wondering what exactly was going on, since the movie had been toying a bit already with whether or not divine intervention was afoot. Even knowing it was just a big construct of wood and gold plating, any christian in the crusaders’ position would surely be emboldened by the sight of a huge shining cross on the field. After all the original meaning of the Christian cross was as a symbol of triumph over even the most dire trials, and additionally of phoenix-like rebirth. Prior to Christianity the cross was a symbol of failure and suffering, being one of the worst ways to be killed generally reserved for only the most horrible criminals (and the origin of the word ‘excruciating’). To a Christian it means ‘give me the worst you’ve got, I’ll come back with the best.’

Some folks who protested the Xbox Live swastika ban suggest that some folks may find other symbols such as the cross offensive, and indeed it’s not something that’s appreciated everywhere you go. I avoided the aforementioned movie for quite awhile because I thought it was a pro-crusades movie (in actuality it’s quite an interesting story on the nature of faith and moral ambiguity, provided you pick up the director’s cut so they have time to tell it properly). As for our ‘modern’ world, there’s still far too many places where people kill each other for practicing the ‘wrong’ religion.

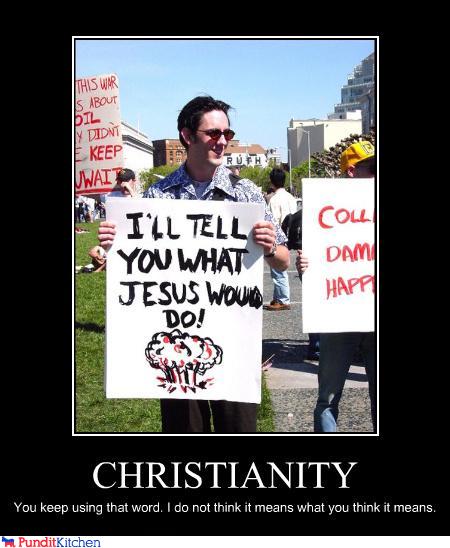

And I’m not just talking about Christian missionaries who face a very real threat of horrible painful death while they go about trying to help earthquake survivors or assemble makeshift hospitals. ‘Conversion by the sword’ thankfully isn’t standard procedure anymore, but a lot of folks would quite logically find the cross offensive when they see people displaying crosses being overly pushy with their views or throwing stones at ‘nonbelievers’ or making statements from public office that non-christians shouldn’t be considered American citizens. I can already hear someone in the audience shouting ‘no true scotsman’ but dagnabit I wish people would stop using symbols I like while they’re going about being tremendous jerks.

So, how about that swastika. While it’s a safe bet that the folks who want to toss the crooked cross around in an FPS inbetween teabagging and homophobia are aren’t really in it to reform public perceptions of the swastika (or anything else, for that matter), there are people who really do want to see the symbol gradually shed of its negative connotations. Like the ski mask, its origins are rather more benign than its modern associations.

In original sanskrit the word svastika roughly means something auspicious or quite lucky, not unlike having a four-leaf clover on a pendant or hat. Like many great memorable symbols it’s easily identifiable and simple to recreate. It goes well with artistic decoration because it can easily be used in a large repeating pattern, and seems to be found in a plethora of early civilizations worldwide. The vaguely-circular nature made it popular with eastern philosophies that frequently refrenced reincarnation and the cyclic nature of the universe (life and death, day and night, seasons, tides, breathing, etc.). It was also frequently used as a symbol of strong forces of nature, referred to in western civilizations as a sun cross or thunder cross. Even some ancient native american tribes have been found to have used it in the past with similar symbolism. Being a symbol for the best and most auspicious powers of the universe it seemed a natural fit when someone needed a symbol around which the aryan ‘master race’ could rally. This might not have been so bad if all they wanted to do was lay claim to their own personal “we’re awesome and everyone else can bite it” logo, but then they went off and tried to take over the world and things just went to pot.

Nowadays the swastika is of course a good deal less popular in the western world. In Germany displaying the swastika in any form is understandably illegal, and jokingly asking if anyone’s seen Kyle while demonstrating about how tall he is can get you up to three years in prison. In America the symbol as well as the word ‘nazi’ are popularly slapped upon anything folks want to mark as unambiguously evil, especially in our entertainment. The long reign of the WW2 FPS games (which is thankfully coming to an end) went on longer than the actual war they glorified. It’s also a popular choice for folks who want to quickly and efficiently offend as many people as possible, spray painting it on walls or tattooing it on their faces to show how much they hate society or something.

As for the matter of the bans, agree or disagree the fact is Microsoft is legally in the right on this one. It’s easy to forget that Xbox Live is private property, not public. You’re a guest in their house. If you were hosting a LAN party and you felt someone was being a goof you’d be in your right to ask them to either knock it off or depart from your house. Having a swastika on your gamertag or sprayed on the wall during a deathmatch is sorely lacking in the context and open dialogue you’d need to actually get people to not dislike the swastika. There’s better ways. Modern practicioners of Buddhism and Hinduism still use the swastika with its original benign intentions, and as religions go they’re some of the most laid-back easy-going peaceful people you’ll find around the world. If not for the nazis mucking it up you’ve gotta admit it would be a pretty cool symbol to hang on a pendant or draw on your notebook when english class gets boring.

I’d now like to make a semi-clumsy segue back to the matter of swastikas in entertainment, particularly American entertainment. Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds features the titular Basterds hunting down those nasty nazis inbetween the traditional Tarantino fare of top-class character-driven storytelling. I don’t know if Tarantino intended this or not, but I also found it to be an interesting wielding of symbolism and characterization that I’m now going to use to close out this ramble.

In most shows a quick way to make it clear who we’re not supposed to root for is to give one team nazi-like qualities. If you see folks marching about the streets in shiny-booted formation, dressing in matching colorless uniforms in large groups, or calling themselves ‘stormtroopers’, it’s a safe bet that these are the guys the plucky heroes will have to overcome by the third act. So much the better if you have actual nazis in your story; WW2-era German military uniforms are all the exposition you need to know that the folks visitng the farmer’s house in the opening scene are up to no good. And while the commercials seem to imply that the movie is all about the Basterds on a non-stop action hero rampage agains the nazi hordes and Hitler is more or less played by Cobra Commander (which isn’t too far removed from the truth depending on who you ask), Tarantino also does something with the nazis that I found to be both innovative and compelling; he made them human.

A majority of the protagonists spend the movie trying to take down the third reich as is all well and good, but one of said protagonists is a young nazi marksman dealing with suddenly being a famous war hero complete with a movie deal. Over the course of the movie he wavers between being proud of fighting for what he believes in and being dismayed by having footage of him killing people being put up on the silver screen as entertainment. There’s also a scene in a bar roughly midway through the show where some German soldiers are having a drink and celebrating because one among them has just recently become a father. They share stories and play pub games and laugh together and for a little while you can almost forget that these folks are part of an oppressive regime that brutally and systematically murdered millions of people. The movie almost seems sadistic in its characterization, one moment having you cheer on the Basterds as they carve swastikas into the foreheads of captured nazis to force them to wear the mark of their chosen allegiance for the rest of their lives, the next filling you with grief for the newborn son whose father won’t be coming home because he was killed by a ragtag band of jewish commandos.

The point I’m gradually circling like an indecisive shark is that a symbol can be chosen for one meaning and later declared to have many more, but the most effective factor defining any given symbol is the sort of people who rally behind it. When you hold up a symbol you’re saying in shorthand “I believe in the things that I believe this symbol stands for.” What you might not consider is that what you’re also saying to others is “I believe in the things you believe this symbol stands for.” There’s a point I like to bring up for my CCD class around Easter time that for our Easter Vigil mass we gather outside and light the big pascal candle, whose flame is kept lit in the sanctuary all year round. Everyone gathers around the pascal candle with small handheld candles, and the flame is spread from one candle to the next and shared amongst the group as a metaphor for the way we can share salvation with each other. That little flame can keep your hands warm and help you find your feet on a cold dark night, and if you share it carefully you can help others do the same. By contrast if you jam your flame in people’s faces with little or no explanation and then take offense when they decline your further offerings you may need to rethink how you’re representing yourself and your symbols. The surest way to make folks equate your symbols with good behavior is to have it handy while engaging in good behavior. Preach always; when necessary, use words.

Can I use your blog in a Psychology of Religion course I am teaching? You have profoundly integrated a number of concepts that I try to get across to students from gaming symbols to religious symbols. I would appreciate your permission to use it. Email me and let me know asap.

I’m glad you enjoyed the post, and I’d definitely be interested in seeing it used to aid education. I’m cool with you using it for your class so long as I can have a gander at what sort of lesson plan you have in mind to see how it’ll be applied. Maybe even collaborate on it if you like. I have a bit of a hobby of studying how various religions and philosophies shape the world and the way people interact in it. A good way to get to know people is to try to figure out why they think what they think, after all.

interesting and i’ll getting it.

i just want to know whats the meaning of the symbol right after the cross???

Which one do you mean? There’s a couple crosses.

Whats the bottom right symbol mean?

A bit of research says it’s a Horn of Odin from the religion Asatru. The following links look like pretty good sources for further research. http://paganwiccan.about.com/od/bookofshadows/ig/Pagan-and-Wiccan-Symbols/Triple-Horn-of-Odin.htm – http://paganwiccan.about.com/od/pagantraditions/p/Asatru.htm

do you know what the top right symbol in your first picture means?

http://www.religionfacts.com/hinduism/symbols/aum.htm According to this site it’s called an Om or Aum, a symbol from Hinduism. Composed of three sounds (a, u, m) it represents several trinities and is essentially a symbol of the Hindu view of the shape of the universe. The super short version would be to say it’s about the cosmic vibrations that resonate through everyone and everything, making all of us a unified whole.

Greetings! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My blog looks weird when browsing from my iphone4. I’m trying to find a

theme or plugin that might be able to fix this problem.

If you have any recommendations, please share. Many thanks!

No idea, sorry. There’s a lot about wordpress functionality I don’t know though. If you go to the main wordpress.com page they may have a tech support contact or something.